Voyage Denver

6/5/2025

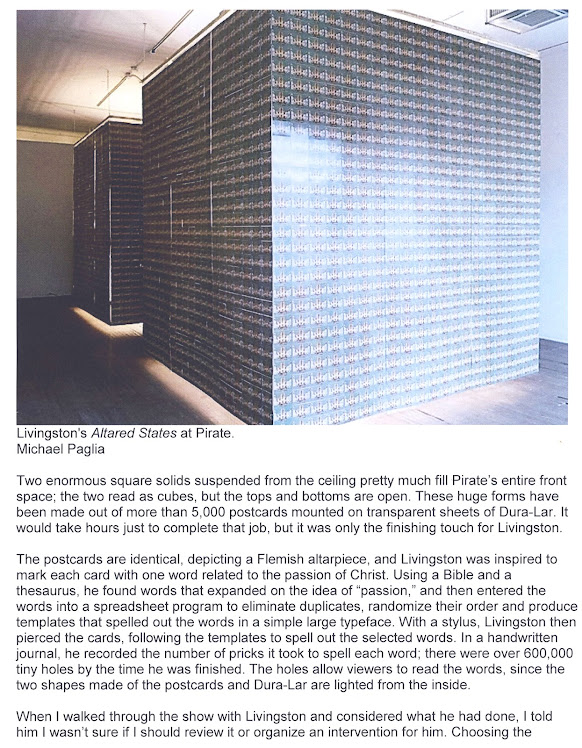

Conversations with Charles Livingston

Today we’d like to introduce you to Charles Livingston.

Hi Charles, we’re thrilled to have a chance to learn your story today. So, before we get into specifics, maybe you can briefly walk us through how you got to where you are today?

I was born in Woodbury, NJ in 1967. Growing up I always knew that I would enter the creative field. I didn’t know how. I had severe asthma most of my childhood and was bed-ridden at home or hospitalized because of mold spores that grow at sea level, at least that is what the doctors determined. With a lot of time to myself, isolated in a room, I remember studying the things around me, really observing and then retreating inward and letting my imagination take over. With a pencil and paper I self-entertained by writing and drawing. At home or hospitals I always had a TV, so that had big influence on how I experienced the world. I spent a lot of time with my grandparents because of asthma. My grandfather had a workshop so I watched him fix and build things and he was always willing to let me help. He was also a self-taught nutritionalist, or scientist (curious in many fields), who studied specific diseases like MS and AIDS and how to possibly cure them. That led to him studying amino acids, the building blocks of life (as he put it). Early on, he started a business selling amino acid formulas to body builders. He was extremely giving and empathetic and wanted to help cure people and this made him terrible at running a business because he always gave the stuff away. He had a microscope that I spent many hours studying plants from the backyard. This may be where my interest and understanding of micro to macroscopic interconnection and interdependence stems. My grandmother was a nurse during World War II so she took it upon herself to look after me when I was bedridden. She had a collection of artifacts from India and other parts of the world. My grandfather built her a huge wall size cabinet to showcase the collection. She also had many landscape paintings of alpine scenes and the four-hundred year old flour mill where she grew up in Germany. She was an avid pianist. There were at least two pianos in the house and she started giving me lessons at 5 or 6 years old. My grandparents had an old cast iron ribbon type writer in the study that I spent hours at writing short fiction and sci-fi stories. There was a lot of influence growing up in this environment at an early age.

Flash forward, the family (parents, grandparents, brother and sister) moved to Longmont, Colorado because of family health issues (mainly respiratory health) in 1980. The air was much cleaner along the front range in the 80’s. I spent much of my time in high school skipping classes so I could spend time working on paintings and drawings in the art room. Class would end and I would keep working and the teacher would ask if I had another class and I always said “no”. After high school I tried getting into CU but couldn’t pass the entry exam because my comprehension skills were horrible. I would spend five to ten minutes on a word problem trying to understand what they were asking. As an artist or creative, you don’t always think logically, you think outside the box, two plus two always equals something other than four. I had a slew of different jobs over those years, grocery store clerk, convenience store clerk, fast food, and working on an assembly line moving computer parts. During this time as a teenager and into my early twenties I tried ignoring the art side of my life because I was encouraged to get a ‘real job’. I worked and spent a lot of time outdoors hiking and running mountains west of Longmont and started entering 10k races. When my parents divorced I moved to Coal Creek Canyon with my mom. The mountain running took a toll on my shins, so I took up mountain bike racing since Coal Creek Canyon was the perfect training ground. I won uphill events and some long distance cross-country races. Having asthma and knowing how to function when short of breath really helped me push harder than a lot of the other riders. This was the early 90’s and mountain bike racing was a new sport so they would combine the race classes. Pros lined up in the front and everyone else behind. I was classified as an Elite, one step from Pro level. There is a big leap from Elite to Pro. Those guys were naturally gifted and made it look easy. I was always struggling but still thought I could be a pro bicycle racer. In Aspen on a downhill section of the race I crashed so hard I almost blacked out but was able to make it back to the start line and catch the last van headed back to town where the ambulance guys patched me up. That was the end of my mountain bike racing, so I took up road racing and excelled in uphill events like Mount Evans and The Iron Horse Classic in Durango. Again, the Pro cyclists were on a different level.

I was newly married at the time and my wife graduated from Metro State College in Denver and her friends went to Metro so my next move was to attend college for something I ignored for many years but was interested in and knew how to do, ART. Also, an old high school friend called out of the blue asking if I was interested in a job designing rugs for a company at the Denver Design Center because he was leaving and I was the only other artist he knew. I was just laid off from my previous job and was immediately hired on his recommendation but had no experience designing rugs. For the first year I spent a lot of time moving and delivering rugs and organizing carpet samples until I learned how to work with interior designers and their clients, reading architectural plans, specing, and render custom rugs for manufacturers in India and the Philippines. Once the designers got to know me business picked up and my rugs and stair-runners ended up in some wealthy spaces both local and abroad. Some of these clients had art collections. I remember one woman in Vail, she didn’t realize how much her Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns paintings and prints in the hallway were worth or who these artists actually were. Her brother was an art dealer in California in the 60’s and told her to buy them because they would be worth something someday. I found that amusing and have run across more than one collector who doesn’t know what they have. Getting this design job and going back to college as an adult was a life-changing experience and opened my eyes to a whole new world. I would sit in the library for hours between and after classes pouring over the art books. I wanted to know more than my professors and that led to some amazing one-on-one conversations. I became focused on art theory and history and the underpinning ideas of my work became very philosophical. At Metro I took the basic art classes in printmaking, painting, drawing, ceramics, etc. to understand the processes, knowing I could continue on my own if I wanted to pursue a specific medium. I found it was more important to know the history of art and know where art has been so I would know where it is going and what I could do differently. That attention to academia landed me an independent study for a semester in Tuscany, Italy where my wife and I rented an apartment in Cortona studying Italian art history from three different periods. I was writing papers for class, drawing and painting everyday and traveling around Italy. When I came back I finish school, continued designing rugs, and was having exhibitions of my paintings and assemblages in galleries around Denver.

Once I graduated from Metro State College I wanted to get an MFA. One of my professors said there were MFA programs that waived the tuition if you worked for the department. My brother was living in LA at the time, so I checked out UCLA but financially and the location was not feasible, plus I had been told my paintings had an east coast vibe. I checked out schools in Boston, Rhode Island and Yale. I applied but couldn’t afford these schools and they didn’t offer tuition waivers. Plus, these schools stipulated, if you started as a painter you had to finish as a painter. I didn’t like that. I was always doing things other than painting like photography, assemblage, and bookmaking to better explore my ideas. The concept was always more important. I always considered the art object as a document to convey an idea and to explore an idea from different angles. I took a tour of the University of Connecticut and talked to a couple professors. My first question during these tours was, “can I work with other departments on campus to develop my work”. UConn was very open to my approach and had no restraints. The studio spaces were on a satellite campus close to the main campus, quiet with no interruptions and large. At UConn in exchange for a tuition waiver I was an assistant teacher and learned how to teach beginning drawing the first year. The second year I worked as an assistant to the on-campus gallery curator, Barry Rosenberg. It seemed he knew everyone in the art world and bought work for a local collector. I spent most of that time using the university van to pick up high end contemporary art in Chelsea, NY from galleries and hang the work at the UConn art department gallery. That job gave me the opportunity to meet gallery owners in NY, learn more about the art business, what happens behind the scenes, attend openings and meet some of my favorite artists like Richard Serra, Chuck Close, Mariana Abramovic, and Gregory Crewdson. By the end of my MFA I stopped painting and was focused on installations, conceptual and processes art, and spent half the time in the print studio doing experimental stuff like inking string and printing on cellophane. The print professors were nervous that I was going to ruin the presses. I was very meticulous in understanding materials and how to adjust a press for my unusual way of making mono-types. They all liked clean prints. I liked blobs, splotches, imperfections, and was studying John Cage, embracing his definitions of chance and indetermination as a way to make art. I would get these faces and cringes from students and teachers. I knew I was on to something.

After my MFA, rather than come back to Denver and that was always the plan, we moved to Philadelphia were my wife had a close friend. I started showing my work at galleries in Philly and worked for the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a cashier in the retail store. After a couple of years I became the retail online and mail-order manager in the back offices. That job gave me free rein to wander the museum and talk to all the departments and wander into exhibitions while they were being installed. I spent a lot of time in the modern/contemporary wing studying impressionist paintings, the Cy Twombly room, the Brancusi room, and the Duchamp room with the Large Glass and Etant Donne (the wood door with a peep hole). Ann d’Harnoncourt was the museum director and on the John Cage foundation. Once I knew that, we had some interesting discussions in the museum halls. Working at the PMA I stumbled upon the work of Marcel Duchamp. This became an amazing opportunity to try to figure out this enigma of an artist and his artwork. The Large Glass always perplexed me. The more I thought I understood about this work the less I understood, so his work always kept me engaged. During the years I worked at the PMA I did three major photographic projects about different aspects of the art and museum addressing the passing of time. One is about Duchamp’s Large Glass, one about a specific view in the Rodin Museum (the PMA manages this museum), and one about the exterior of the PMA itself. All these works have accompanying sound recordings of people conversing in the museum. I’ve only shown one of these projects, over 1,100 photographs, at Pirate Contemporary Art. Currently I’m showing a smaller photo project shot in the PMA at the Lincoln Center in Fort Collins. The years at the PMA allowed me to meet a plethora of artists while they were installing including William Kentridge, Ellsworth Kelly, Bruce Nauman, Frank Gehry, and Cai Guo-Qiang who did a huge lotus flower firework piece on the face of the museum as a tribute to Ann d’Harnoncourt just after she died. An amazing and incredibly moving piece that was ignited and happened at dusk.

My wife and I decided to move back to Denver and we bought a place in Lakewood. I joined Pirate Contemporary Art as soon as we moved back to Colorado and started showing. When I was a student at Metro State College Pirate was the place where all the cutting-edge cool shows were happening, so that is where I would hang out on Friday nights. My academic education was at Metro, education on becoming a practicing artist in Denver was by having conversations and mixing it up with other wild local artists. Going to openings was extremely beneficial in navigating the Denver art scene.

I always wanted to teach at the school I graduated from and landed an adjunct job at Metro State University teaching drawing. A little later I started to teach painting courses for Carlos Fresquez, my undergrad teacher when it was Metro State College. About eight years later I had a heart attack and that was a life altering experience. My wife and I went our separate ways. I felt I had an aspect of myself that had to be explored, one that I had suppressed since childhood. My values shifted and the artwork shifted slightly. Now I only do shows that are very specific to the type of work I do or that give me the space to show in a most impactful or impressionable way. Environmental context is very important if you want to convey an idea with clarity and without distraction. The major body of my work is process and time-based and some pieces take years to complete. It is difficult to find venues to show large scale pieces, most often they are submitted as proposals because I have never seen them fully installed and complete in a space. Installing a new work for the first time is as interesting for me as it is for any viewer or experiencer seeing it for the first time. The work most often deals with issues of accretion and accumulation and is malleable enough to be reconfigured and respond to any space. There is an organic characteristic to it. Over time a piece can change and redevelop into something slightly different, expanding on the original concept. With some projects I like to explore more than just the visual aspect. Art becomes more memorable and impressionable when multiple senses are activated. As for being time-based, my Infinite Drawing Series has been rotating on the drafting table for over twelve years and I’m currently working on a language piece that will have taken about two years to complete, if ‘complete’ is a thing. Some projects like the Infinite Drawing Series can go on until I run out of materials, cannot sustain working on it any longer, or I expire. I find the time-based aspect of my work intriguing, a document of my time spent making, the product of a single organism. Usually the ending parameter or parameters of a project is the availability of the materials or how far a certain material or project can be resurrected or exhumed and reconfigured. Some people proposed that I make the work larger and employ a team to make it faster in order to meet exhibition deadlines like some artists that appear to be working in a similar genre. For myself, speed is not imperative, making more in a shorter amount of time would not allow for the time required to achieve any type of meaningful inner transformation (I may be revolting against a society that wants instant gratification, wants to go faster, and have more). The intent and purpose behind what some artists are doing is very different from what I am doing. Plus, my projects are personally developed experiences. Trying to share this with another would not translate the same especially if they are hired to do the work, that would taint the experience. Each person needs to find what causes them to turn inward, to introspect and search for their best self in order to radiate that out into the world.

As a side, I also show representational art under a different name because that work is so different from my non-objective conceptual and process pieces. That body of work and how I present it seems to be another outlet for self-expression that keeps me grounded. Recently, through introspection and observation it seems that one body of work exposes the problem and the other the solution but I ‘m not sure which one is doing what at any given moment.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

The journey has not been smooth, but without difficulty it would not be as

interesting and there would not be as many chances for self-discovery and

growth. Part of the difficulty has to do with making installation art that

looks so diversified and the amount of time required to make it. Someone one

said “you make art for artists”. Eventually I understood what that meant. Art

that addresses people who know the history of art, that conveys meaning about

the human condition based on knowing what has been explored and presented

before. I am trying to unearth or expose new territory but the truth is we are

a product of what has come before and are responding to that, even if we don’t

realize it. The best I can do at this point is to shelf my knowledge of art

history and theory and not allow it to sway ideas I want to explore. For now, I

think I am making things based on a more complex navigation of being human and

my relationship to the world. I believe each individual is the center of their

own universe, everything revolves around you, your consciousness, you are the

only thing you can know, and if you study spiritual aspects of being human, that

is questionable. Another problem that makes the road difficult is that I am not

business savvy. I inherited a lot of characteristics from my grandfather. My

work is all consuming and since it is time-based I find there is little time to

sit at a computer for hours looking for exhibition opportunities, applying for

grants, residencies, etc. I know selling is something artists need to do in

today’s world to put a roof over their head and be “successful”, but selling

has never been a concern. I don’t know if that is a fault, to not be focused on

finances, but it has allowed me to be uncompromising in what I want to make as

an artist. In fact, if my work sells I think l am doing something wrong because

it is not challenging established norms and progressing cultural, social and

spiritual ways of living. I definitely believe in artists making a living at

what they do and I would immediately entertain the idea that some gallery, a

gallery that understands my values, would like to represent me and sell my

work. It is difficult for most galleries to sell work that looks dissimilar,

though the underlying issues or concepts are the same. I believe in selling

ideas or concepts over the art or artifact. The artifact (in my case a

document) is a tool or vehicle for engaging in deeper discussions to better

society, not just a trophy on a wall or something that just makes me feel good

or goes good with the furniture. And there is the time-based aspect where some

projects take years to bring to some type of conclusion. I will show certain

projects at different levels of completion. At any one time I am working on 2-3

projects with different parts of the house devoted to different pieces. These

are some of the issues that have made the road rough, but I wouldn’t do it any

other way. I feel true to myself and vision and that sincerity comes out in the

work as it is expressed in my experiences surrounding it and knowledge of it.

Part of the energy that emanates from a work of art resides in that sincerity.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

I’ll turn to my short artist statement to help clarify what I am concerned with

and doing. “My work most often documents small repeated actions over time

resulting in physical accumulations of objects or mark making. These processes

are meant to trigger introspective moments causing internal transformation and

heightened perceptual awareness.” What I am creating for myself in the studio

are projects that allow me to introspect and meditate. To see what I can endure

and how I can get past the physical aspect of repeating an action with some

medium or materials for long periods of time. For most artists, the process of

making is a cathartic experience. For myself, each project is an opportunity to

discover and transform from within. I believe a lot of the world’s problems

(social and political on all levels including some physical health) stem from

not being able to face ourselves and understand how positive transformation

from within radiates out into the world. Simply leading by example can make the

world a better place (I’m borrowing a little from a profound and succinct

statement by the artist Lawrence Weiner). In this sense my projects are

designed for my own spiritual well-being and health and when shown publicly

they become metaphorical examples of what we are doing everyday such as getting

dressed, driving to work or mowing the lawn. The intention is to show how a

person can use their daily activities as a way to introspect and transform if

they are mindful and pay attention. Ultimately most ground-breaking art or art

that has made of significant difference is about causing a perceptual shift and

it may take the form of an epiphany or awakening. On the other hand, in order

to convey this idea that anyone can transform from turning inward, I study

interconnection and inter-dependency, how systems are dependent on one another

for either survival or pure existence. Looking at maco to micro accretion

(accumulation) of things is relevant to how the universe is constructed, from

sub-atomic particles and DNA to entire galaxies. Small repeated actions add up

over time and make significant lasting changes and/or accumulate to a point of

physically taking over a space. Causing introspective moments (perceptual

shifts) through the study of interconnection or inter-dependency are

interrelated aspects.

What sets my work apart from other artists doing conceptual, process or serial types of art is that it must be made by my hands. I will never use a team of people or machine to make the work, that would negate the point. It is about what a single organism can do when focused for long periods of time. This way of making the work retains an organic element of imperfection, an aesthetic attribute imbued with the imperfections of a single human touch that can be sensed by the viewer. Any mistakes made while engaged in the process of making usually reappear throughout the piece and in essence become an integrated signature to the work. If a viewer pays close attention to what is happening, observes and studies a piece, they will eventually enter the work at a completely different level and notice things happening on a much smaller scale.

Networking and finding a mentor can have such a positive impact on one’s life and career. Any advice?

Going to galleries (most often openings) and museums has been the most

beneficial way in getting to know the creative community. I am always running

into someone I know and they introduce me to someone new. Over the years all of

my connections have been made this way and it allows people to get to know you

and your work much better. Ask questions and always meet someone new at an

event and find out more about them. I learned a lot about networking as a rug

designer, mediating between interior designers and their clients and attending

those events. Connect with people who enjoy your work or understand it and

along the way you discover a mentor. I would never spend time searching for a

mentor, I think it is a waste of energy that can be spent making art and

meeting new people. Most mentors naturally appear or present themselves when

you are not searching. You will recognize when someone is available to help guide

you, when a connection occurs. Sometimes you don’t realize that you had a

mentor until years later. My first mentors appeared in college and it was not

something I was seeking, they knew I was interested and started challenging me,

to push my thinking and art in new directions as well as giving me good advice,

some of it not always art related.

InLiquid

Philadelphia Introductions: Charles Livingston

By Andrea Kirsh

May 2, 2007

Charles Livingston spent a long time working against the beauty of his art; it was a quality that his professors in graduate school criticized. Then he stopped thinking about it, which is good, because beauty inheres to his work. This would not seem obvious from his method, which involves rigorously systematic procedures which the artist sets up. In description these procedures recall Sol Lewitt’s working method, which specifies that a particular type of line be repeated across a specified surface. But where Lewitt’s work has a consistently geometric quality, Livingston’s tends towards the organic.

This organic quality is partially a matter of his materials. Livingston favors drawing on tissue paper, which he layers so that the resulting work is a product of a slow growth and one drawing is seen beneath another, rather like skin. In 2003 he produced accretion in form which consists of six 16 x 20 inch panels. Each bears multiple layers of tissue paper on which he has drawn in pencil; the mounted drawings were then covered with a synthetic varnish, which yields a soft glow. Each of the six started with a different mark, which was repeated over and over again, until part of each drawing approached a dense black. Some of the marks are circular, others relatively straight, but they have none of the precision of lines aided by drafting tools. These obviously hand-made lines are distributed irregularly across each sheet; the results are thickets of lines, and forms with slightly hairy borders.

accretion in form initiated an extended period during which Livingston has set up exercises to explore just what a drawn line is. All of these involved lengthy repetition, sometimes increasing sequentially across the length of a piece or in series. His use of repetition derives from several sources. One is the artist’s experience with factory assembly-line work. Another is the repetition involved in meditation. It also comes from his interest in feminist art of the 70s and its exploration of the repetition involved in the sort of maintenance work which has traditionally been women’s lot. These were a particular focus of Mary Kelly and Mierle Laderman Ukeles; the washing-up is never really finished. Livingston has stated that repetitive action can be considered a sustaining action that contributes to the construction of our realities. In this, repetition is related to natural development and growth, and hence to time.

Livingston has also inserted an element of chance into his methods; this was directly influenced by the ideas of John Cage, and usually takes the form of shapes generated by dropping rubber bands of varying sizes onto paper. He then subjects these fortuitous forms to a series of highly-structured variations. He is currently working on such a sequence which he calls infinite drawings, where each drawing begins with tracing paper placed over a previous one. For the original drawing he dropped ordinary rubber bands in a grid format across the surface of a sheet of 18 x 24 inch tissue paper and drew the outlines in black ink; he colored the areas where they overlapped in pink. This produced an irregular pattern with arcs in some of the lines, punctuated with small pink blotches. For the second drawing he drew straight lines connecting the pink nodes of the first drawing. This design was bolder than the first; it looks like a denser form of the connecting lines in Mark Lombardi’s work. For drawing number three he used two-inch circles to connect the nodes of the second drawing, which yielded a very dense pattern of overlapping circles across the page. Drawing four also used circles, larger ones (five inches) which he centered on each node of the drawing below it, rather than aligning the nodes with the circles’ periphery, as in the previous drawing. The series has no obvious conclusion and Livingston already has the sixth iteration on his drawing-board. He is not likely to run out of ideas, so he will have to create a reason for finishing it.

He likes to display many of the drawings back-lit, and has discovered that if he shows them horizontally, on a specially-constructed light-box, he has the option of layering them, to exhibit their interactions. I saw the first two Infinite Drawings this way, and the overlap created a very fine pattern of straight and slightly-arced lines that resembled cracked egg-shells. In this arrangement Livingston is doing something very similar to a musical theme-and-variations, with the overlapped drawings creating a sort of visual counterpoint. His work also makes me think of a demonstration I saw by Trisha Brown, and her similar method of developing a dance through a set of rules: she associated the alphabet with an imaginary cube surrounding her body, and touched hands, feet, head, or elbows to its corners in sequences determined by language.

The artist has explored his highly iterative method in other forms and media. He has produced several drawings on 150 foot lengths of tissue paper, which he presents as hand-scrolls. He works on two-foot sections and progresses according to an algorithm which he establishes each time. Another work grew in three dimensions: 2200 square feet (accretion variation I) began with a six-inch square of tissue paper placed on a larger piece of Plexiglas, covered with resin, and allowed to dry. He added another piece of six-inch paper, covered it with resin and allowed it to dry. He repeated the procedure 2,199 times. The result is a glowing, soft-edged, honey-colored object, 19 x 14 x 14 inches, which sits on a larger piece of Plexiglas over which resin has spread. Somehow the flow of the resin has caused the four corners to collapse, so the work in no way resembles the regular cube one might expect from stacked paper squares. It is mysterious, with slightly translucent drips on all sides, and sits in a pool of resin that varies in color from pale to dark amber, according to its thickness. And it is very beautiful.

Another serial work involves printing: low-tech monoprints. Livingston inks a large ring of rubber, cut from a bicycle tire, and drops it onto a piece of paper. He covers this with a sheet of plywood and uses the weight of his body as a press. For the next print he drops two of the rubber loops, then three for the one after that, then four, and so on. His goal is to create an entirely black print. The title describes the work in abbreviated form: inking and dropping a circular piece of rubber on paper.

Returning to that vexed question of the beauty of this work, what is its source? Surely it’s a function of Livingston’s choice of materials as well as his hand. It isn’t merely the quality of his lines or the impact of gravity on a dropped loop of rubber, but in how he places them on the page and their relations to each other; he‘s as interested in the spaces between them as in the lines themselves. But it is more: in his sensitivity to light and the subtle implications of transparency, seen most obviously in the layered images. And the consistent use of repetition, of countless actions as regular as a heartbeat. He forces his viewers to meditate on the passing of time and the potential of the whole to be more than the sum of its parts.

No comments:

Post a Comment